PORTLAND, Ore. — The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration confirmed earlier this year that La Niña weather pattern that prevailed for three years has given way to El Niño, a cyclical weather phenomenon during which surface temperatures in the eastern part of the Pacific Ocean become warmer than usual, which can affect weather worldwide.

Cooler eastern La Niña temperatures are associated with increased storm activity in the Atlantic and increased drought in large parts of North America, so although El Niño can bring potentially worse impacts for much of the world, the transition is generally viewed positively for the United Sates. But what will it mean for the Pacific Northwest this winter?

According to KGW chief meteorologist Matt Zaffino, the answer in general is warmer and drier winter conditions, with fewer big storms and less snow than usual in the northern half of the state. Snow in the Willamette Valley is still possible, he said, but Portlanders who are hoping for it might not want to hold their breath.

The Pacific Ocean temperature connection

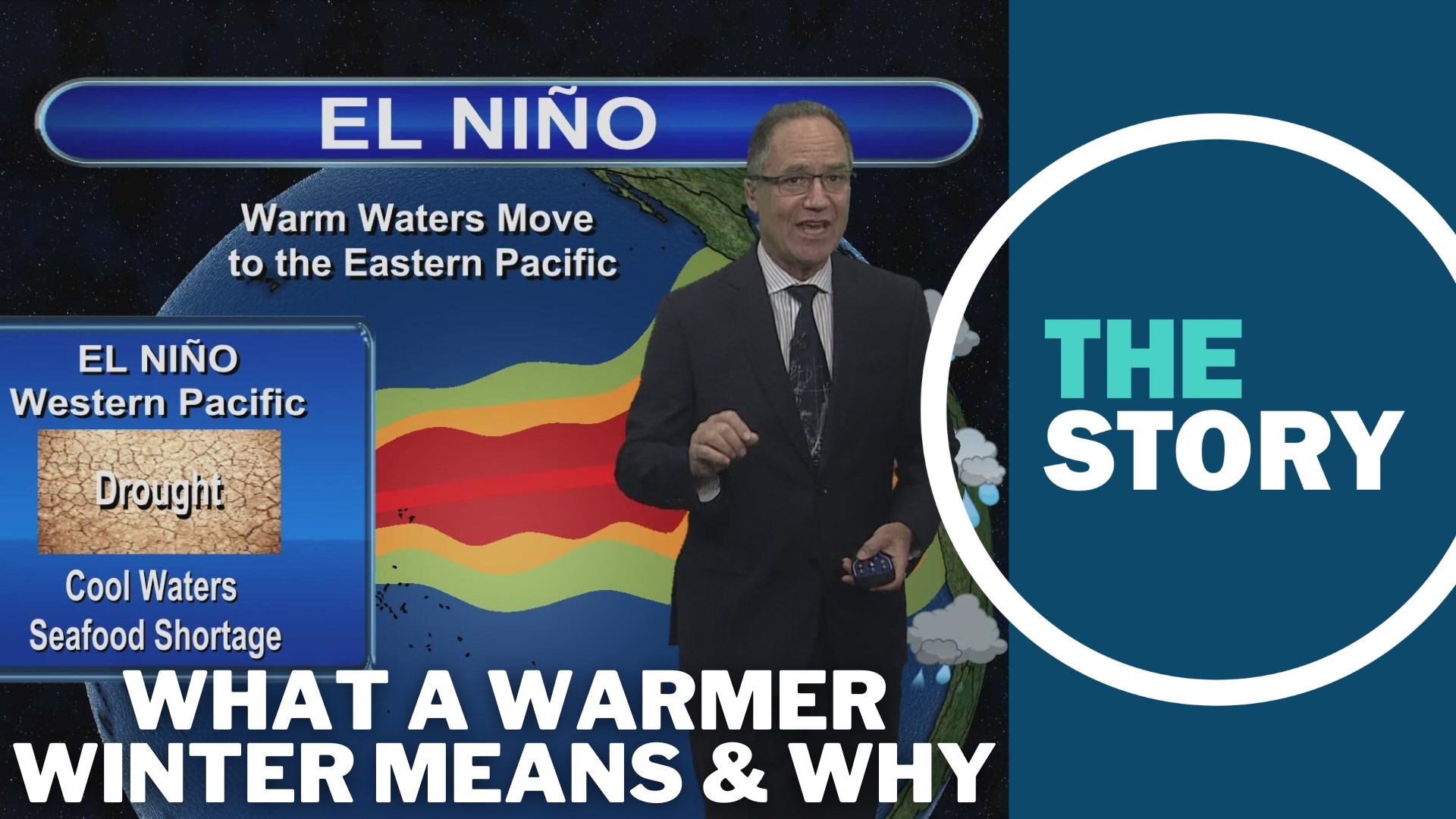

Under normal conditions, trade winds blow west across the Pacific Ocean along the equator, Zaffino explained, which means that warm water near the surface tends to get pushed west, resulting in cooler ocean temperatures off the coasts of South and Central America and a mass of warmer water building up near Australia and Indonesia.

Areas with warmer surface water send more water vapor, energy and heat into the atmosphere, generating increased storm activity and rainfall in the surrounding parts of the planet. During El Niño, the trade winds weaken and the warmer part of the ocean shifts over to the eastern end, bringing greater rainfall to Central and South America — and conversely, the western Pacific region becomes more likely to experience drought, Zaffino explained.

The eastern mass of warm water doesn't extend far enough north to reach the United States, but it has an indirect impact on North America during the winter months because it alters the behavior of the northern Pacific jetstreams, which are bands of wind in the northern and southern hemispheres that blow in an eastern direction.

During El Niño winters, North America tends to end up with a really strong sub-tropical jetstream that pushes more moisture across southern California and the southwestern U.S., Zaffino explained, while the northern half of the continent, including the Pacific Northwest, tends to get a split jetstream that results in warmer weather and fewer storms.

Impact on mountain snow

El Niño generally results in a lower chance of snow in the Pacific Northwest, especially at low elevations, but it doesn't necessarily meant the mountains are going to be left bare in Oregon this winter.

Historical data shows mountain snowfall in northern Oregon may take more of a hit, according to Zaffino — average snowfall at Government Camp from October to March has been about 60% lower than normal during previous strong El Niño years, although there were still some individual months with above-average snowfall.

"There will be periods of snowfall, and heavy snowfall, so my message to skiers is 'when it gets good, take advantage, because it may shut down,'" Zaffino said.

At Crater Lake, snowfall during strong El Niño years has historically been about 111% of normal for the full season. Crater Lake is further south than Government Camp and it's about 2,500 feet higher in elevation, Zaffino noted, and both of those factors contribute the area's more impressive showing during El Niño winters.

"Southern Oregon higher elevations do quite well during El Niño because they're tapping into that sub-tropical jetstream ... that's focused mainly on California," he explained.